(Approx 2 minute 25 second read)

Today, there are many types of karate. But it’s worth saying what often gets left out: it didn’t used to be this way.

.

Originally, karate was a method of self-protection – pragmatic and rooted in application. The shift to having ‘many types’ of karate is not something that just happened.

.

As early as 1908, Anko Itosu, a hugely influential figure in karate’s development, wrote a letter to the Okinawan education department advocating for karate to be introduced into schools.

.

He spoke of karate as a way to build strong bodies and good character – and while his letter also acknowledged its combative value, it signaled a major step toward institutionalizing the art for different purposes.

.

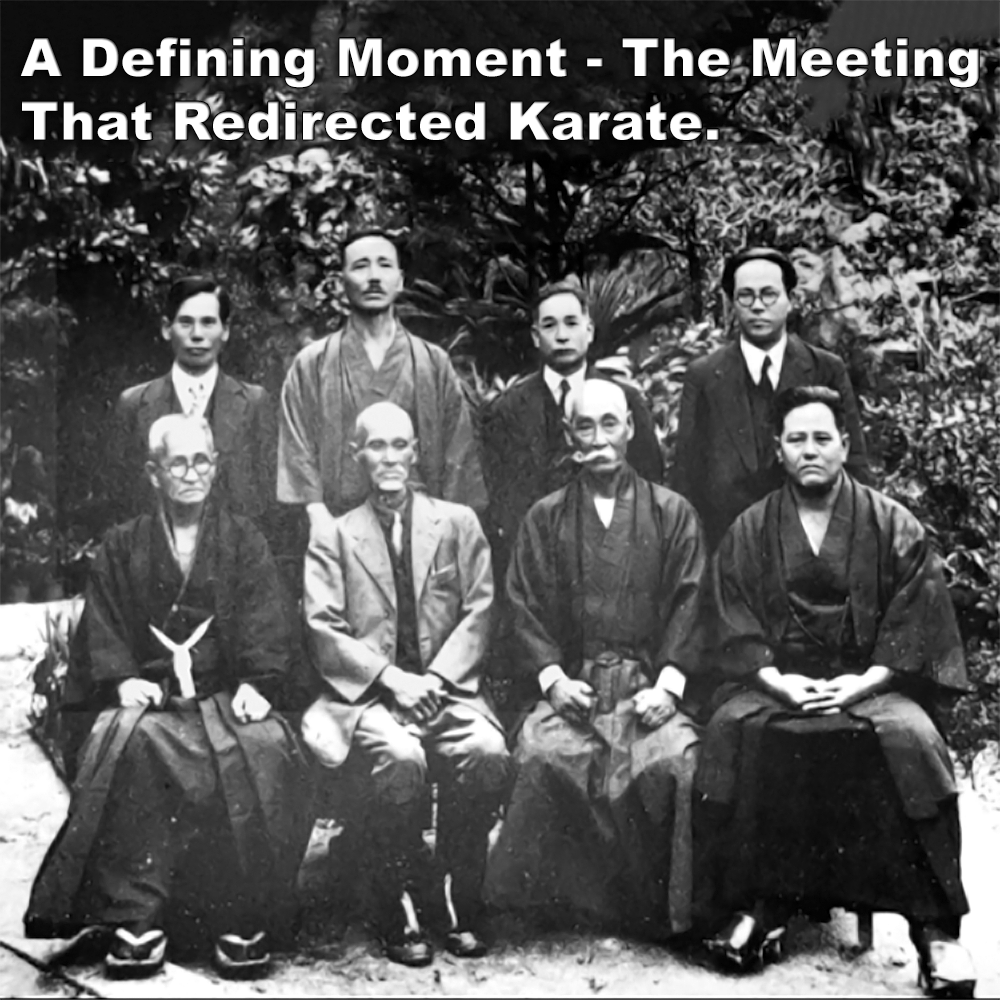

This movement gathered pace in 1936, when several of the most respected Okinawan masters met in Naha to discuss karate’s future.

.

From that meeting came further support for using the characters for ’empty hand’ (空手), instead of the older ‘China hand’ (唐手) – a change already gaining momentum. The push toward alignment with Japanese budo continued, along with a clearer shift toward performance, form, and character development over combative function.

.

From there, karate began to fragment. We now have karate as sport, karate as tradition, karate as art, and karate for health. That’s fine. People are free to choose what suits them.

.

But let’s not forget: it didn’t begin that way.

.

Saying “I train karate for fitness or culture” is fair. But so is saying, “This isn’t the karate that was originally practiced”. Both can be true – and acknowledging that is just being honest.

.

If we’re going to talk about types of karate, then we also have to talk about context. What is being trained? For what purpose? And how closely does it reflect the original intent – if at all?

.

Acknowledging karate’s evolution isn’t about claiming ownership or telling others what they should or shouldn’t do. It’s not about saying one group is more legitimate than another. It’s about clarity. Without that, people end up training for one thing while believing it’s for something else.

.

Context matters.

.

Take sparring as an example. What kind are we talking about? Point sparring, knockdown, full contact, or something rooted in reality-based scenarios?

.

Each has a different goal and different rules – and if you train in one while expecting it to prepare you for another, you’re setting yourself up for failure.

.

It’s the same when people say they teach “self-defense”. But is it really? Or are they just saying the karate they practice includes techniques that could be used in self-defense – while ignoring the parts that truly make it self-protection: the pre-conflict dialogue, de-escalation, avoidance, escape, the presence of witnesses, concern for family members, the potential for weapons, and the legal consequences.

.

Without these, it’s not self-defense – it’s just fighting techniques.

.

Context gives your training purpose. Without it, you’re just going through the motions. So before you call it self-defense, ask yourself: are you really covering what needs to be covered?

.

That’s why context matters – because karate wasn’t created for sport, for belts, or even for health. Its original purpose was survival. The old masters understood this, and when you read their words – like Itosu’s 1908 letter – you see a clear intent: to give people something of real value. Not just movements, but principles for dealing with violence.

.

Karate has changed over time, often for understandable reasons – changes that shifted it toward education, sport, and national identity. But as we adapt it for modern needs, let’s not forget what it was.

.

Because many already have.

.

.

Written by Adam Carter – Shuri Dojo – Inspired by Iain Abernethy

.

.

Photo: The meeting of the masters in Naha.