(Approx 2 minute 45 second read)

I had a couple of questions in the comments on an article I wrote about understanding kata beyond individual techniques.

.

The first was, “When or how does one know when a particular sequence in a kata has actually finished and when the next sequence starts?”

.

The second was, “Which moves can be regarded or seen as ‘stitching’ movements between two sequences?”

.

They’re good questions, but they rest on an assumption that’s worth examining first.

.

Many people assume that kata is made up of clearly defined sequences, that one section finishes, another begins, and that there are obvious joins holding everything together.

.

In practice, kata rarely works that neatly.

.

The idea of dividing kata into sequences is largely something we do after the fact. It’s useful for teaching, discussion, and remembering material, but it isn’t always something the kata itself clearly signals.

.

If we ask, “Where does one sequence end and the next begin?”, the honest answer is often that it isn’t obvious.

.

Now, I’m not speaking about the solo representation here. I’m speaking about using kata as it was intended. Kata does not usually announce a clean ending, except in solo performance.

.

There is rarely a clear moment that says, “The problem is over.” Movement continues, direction changes, the body adjusts, and the kata carries on. That alone suggests something important. The situation being recorded has not yet resolved.

.

This is one reason repetition matters so much. When a similar action appears again and again, it is often taken as a new technique, when it may be better understood as the same problem continuing. The repetition reinforces persistence, not variety.

.

From this perspective, a “sequence” only really ends when the problem it addresses ends. Kata doesn’t always show us that ending clearly, because real confrontations rarely finish cleanly or predictably.

.

This also complicates the idea of so called “linking” or “stitching” movements.

.

Some movements are often described as transitions, ways of getting from one technique to the next.

.

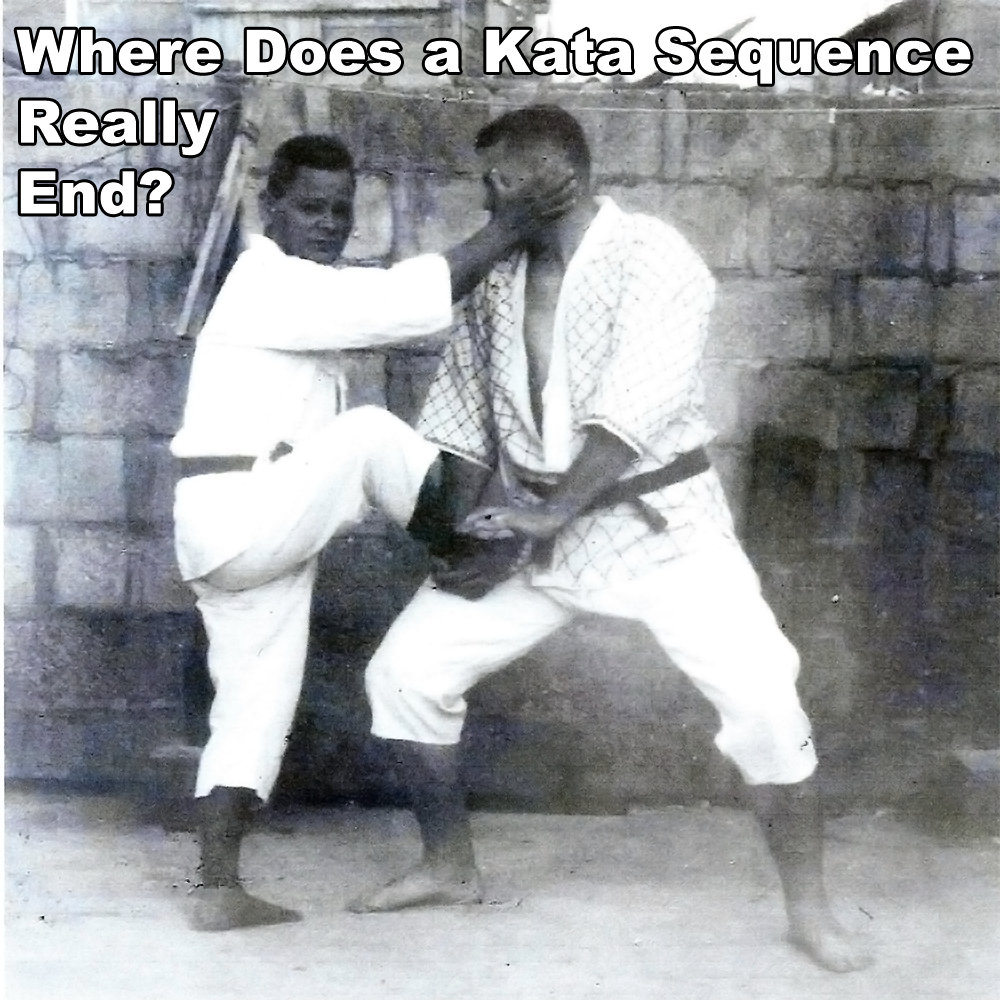

On paper, that makes sense. In motion, and especially under pressure, those same movements may serve multiple purposes.

.

A step, a turn, or a shift of posture might reposition the body, unbalance an opponent, protect vulnerable targets, or create a new angle.

.

Whether a movement is “just a transition” or something more functional depends entirely on context.

.

This is why analyzing kata solely as solo performance has limits. When we work with partners, boundaries that looked clear on paper often blur. Movements flow into each other. What looked like a join becomes part of the action. What looked like a finish turns out to be a continuation.

.

This of course assumes that kata is being used as a response to real violence, not choreography.

.

None of this means kata lacks structure. It means the structure is not always obvious at first glance.

.

Kata is less like a list of instructions and more like a record of movement under pressure. Trying to divide it into neat, labelled sections can sometimes hide that reality rather than clarify it.

.

In my experience, answers to questions about where things begin, end, or connect rarely come from staring longer at the kata. They tend to emerge when the movements are explored with another body in front of you, when nothing resolves instantly, and when the need to adapt replaces the need to label.

.

That’s often when the artificial boundaries disappear and the kata starts to make more sense.

.

After all, no one can know in advance exactly what an attacker will do. If you don’t know how an encounter will unfold, you can’t know in advance where it will end or when something new will begin. Each confrontation is different, and responses have to adapt accordingly.

.

Kata isn’t teaching you how to fight. It’s offering a template of what ‘could’ be useful, not a prescription for what ‘will’ be.

.

.

Written by Adam Carter – Shuri Dojo

.

.

Photo Credit: Shimabuku Tatsuo and John Bartusevics