(Approx 2 minute 25 second read)

Many of us have had remarkable teachers, people who embodied the virtues of a true martial artist. We followed them, often without question, and some even became household names in the martial arts world.

.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: no matter how great the teacher, the system they inherited is unlikely to be the same karate that was once practiced on Okinawa.

.

Some of my articles are written to put ideas out there that challenge what the martial arts are today. Modern karate, or karate-do, is very different from the art practiced on Okinawa before the early 1900s.

.

Bear with me while I ruminate for a moment…

.

Originally a pragmatic fighting art aimed at civilian self-defense against common assaults. Its close-quarters combat methods were practiced in relative privacy, taught in small groups or even one-on-one.

.

The shift toward what we now call karate-do happened in stages.

.

In the early 1900s, masters like Itosu Ankō began introducing karate into the Okinawan school system. To make it acceptable for physical education, dangerous techniques were downplayed, the practice was formalized, and group drills were emphasized. This already started moving karate away from pure jissen (real combat).

.

During the 1920s–1930s, karate was introduced to mainland Japan by figures like Funakoshi Gichin, Mabuni Kenwa, and Motobu Chōki, who helped spread it. Japanese cultural influences reshaped it.

.

The suffix “do” (Way) was added, aligning it with judo, kendo, and other gendai budō.

.

Even the characters for “karate” were changed from 唐手 (China hand) to 空手 (empty hand), reflecting both nationalism and a philosophical shift. More emphasis was placed on etiquette, uniform training, and competition-style sparring.

.

Post-WWII, under the Allied occupation, Japan sought to present the martial arts in a less militaristic light. And karate was further packaged as a sport and character-building discipline, often marketed as a method for health, discipline, and spiritual development as much as for fighting.

.

By the 1950s, the modern budō form was firmly established worldwide.

.

Where am I going with this?

.

This explains why some of the practices everyone trains today may have no relevance, no practicality, and maybe not suitable for the reality of real-world violence.

.

It doesn’t matter who your teacher is, today, their system is based upon the modern version of karate. The dogma you follow is not designed for real violence.

.

Of course there are a few exceptional people who can make anything work in any environment, but it’s not the norm.

.

Trying to place those drills, methods, and techniques into a context where they will save your life is like trying to catch a katana in the palms of your hands. Not only is it foolish, but the context is wrong, and so is the reason for doing it.

.

I’m not saying that a pragmatic approach is the only way to train, or that it is somehow superior. There are teachers out there who still teach in ways closer to the old methods. My point is simply that, whatever style or approach you follow, it’s important to understand the context, why techniques were created, how violence actually happens, and what you hope to achieve in your training.

.

Just practice with your eyes open. Question. However skilled or revered your teacher may be, unless you consider karate through the lens of real violence, how it happens, and this is really important, what it really looks like, you’re forcing a square peg into a round hole. And in the moments that matter, it simply won’t fit.

.

.

Written by Adam Carter – Shuri Dojo

.

.

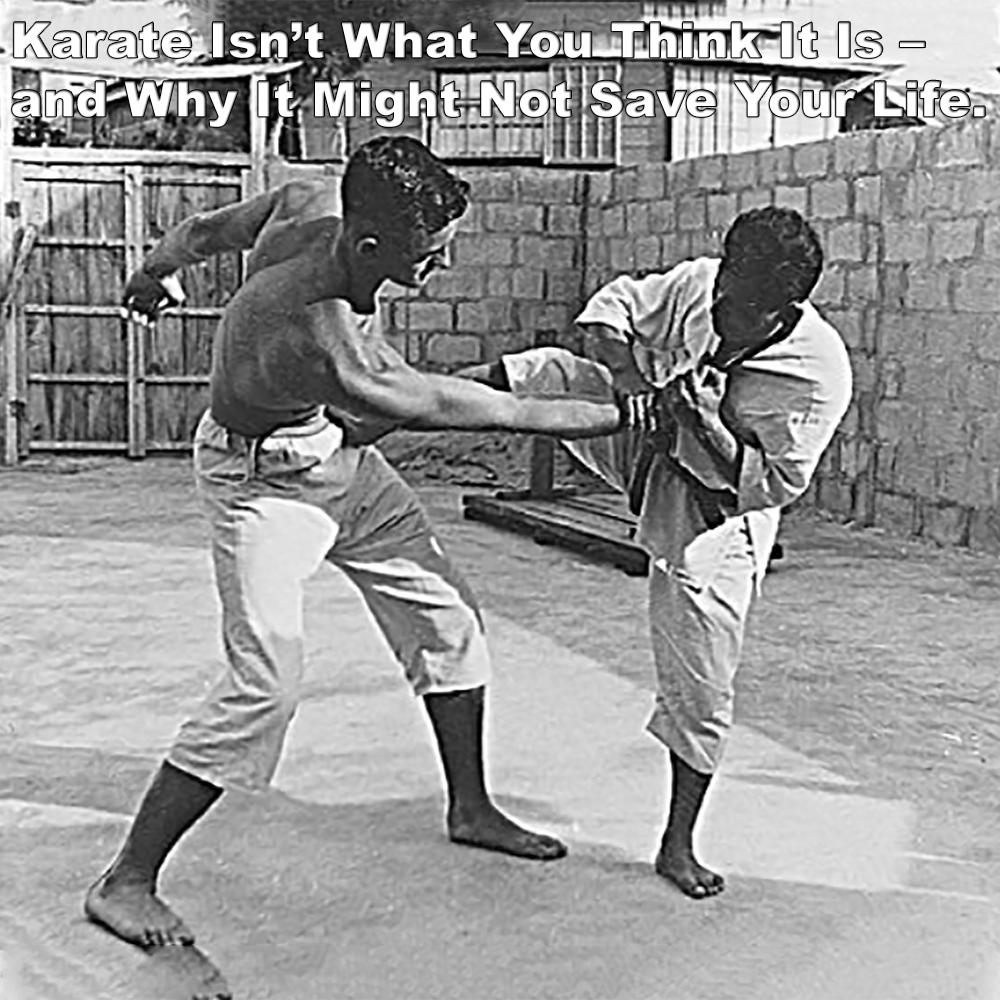

Photo Credit: Tatsuo Shimabukuro & Harry Smith training in mid-20th century Okinawa – when karate was evolving into its modern form.