(Approx 2 minute 45 second read)

Something different.

.

There are many great teachers of the martial arts out there, but how do you become a great teacher? I’m not saying I’m a great teacher, far from it. I’m just sharing what’s helped me teach more effectively over the years.

.

Most instructors fall into teaching as part of a dan grading. Some make it a requirement, others fall into it by chance. I did. I had no desire to become an instructor, but as a brown belt I offered to help my sensei with the children and beginners’ class because he was struggling on his own with so many students. It went on from there.

.

But how do we learn to actually teach the martial arts?

.

Most of the time we follow our own instructors, and them theirs. This system has continued for decades, one generation after the other.

.

And what is it that makes an instructor a success? How do we measure it?

.

In my mind it’s the students who come after you – not how big or popular your dojo is. That could just be down to location, luck, or competitive pricing. The real question is whether your students are becoming proficient in the goals and context you’re actually teaching. I don’t mean tournaments and medals, although for some people that may be their path.

.

I was fortunate enough to be taught different teaching methods outside the martial arts, and one of the most useful was Gestalt theory. I learned it many decades ago when I began teaching students outside of karate. I had already been teaching karate for years, simply following my instructor and his instructor, as I mentioned above. It worked well enough.

.

Gestalt theory isn’t complicated. It’s basically the idea that people learn better when they can see how things connect. When they understand the pattern, the intent, and the context, the movement makes far more sense than when it’s taught as a standalone action.

.

Of course, this doesn’t mean you skip the basics or stop breaking things down. Beginners still need clear instruction and repetition, that’s never going to change.

.

The point is that even while teaching the pieces, you don’t lose sight of the whole. You teach the fundamentals, but you also make sure the student understands what those fundamentals are for, so they don’t just collect techniques with no idea how they fit together.

.

I use it sometimes when I start a new lesson: “Today we’re going to do this… and to achieve it, we’ll need to do this, this, and this.” The students know the goal before we break it down. You show the whole picture, then you teach the pieces that build toward it.

.

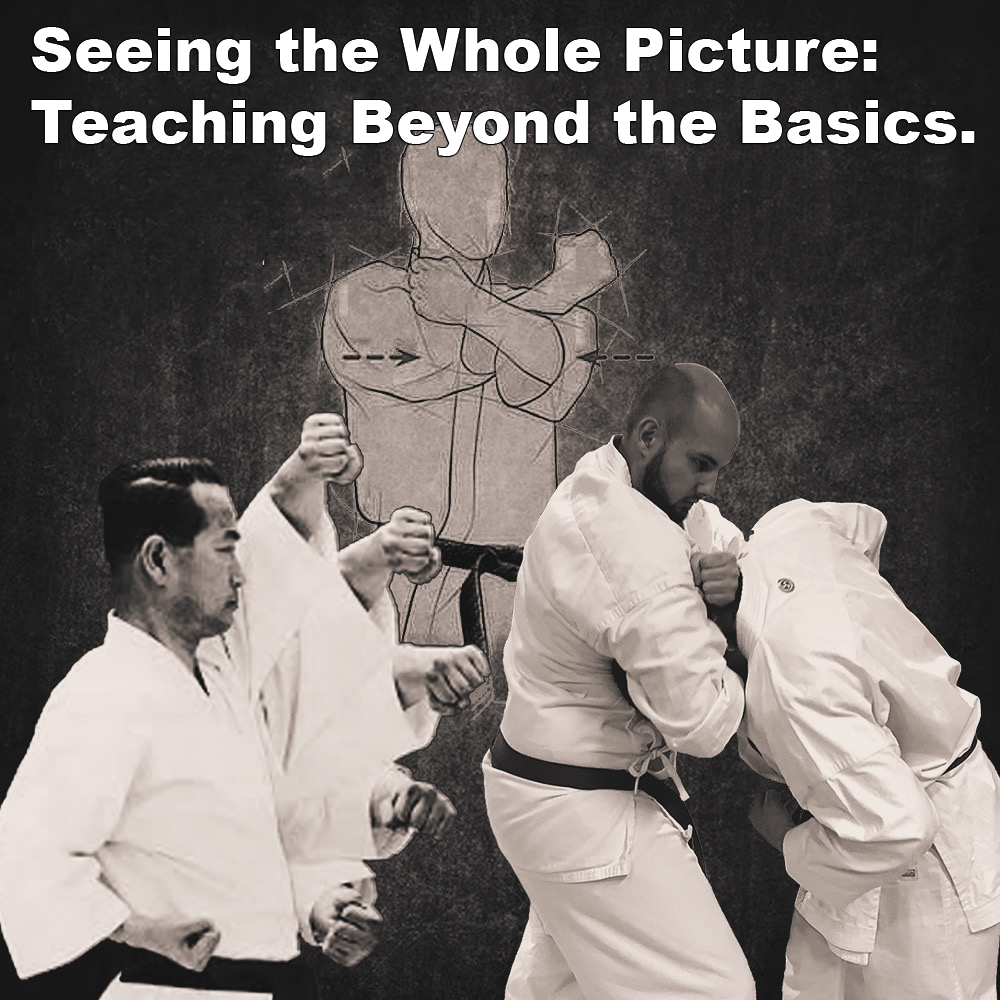

This approach helps students “see the big picture” and understand how the different parts of their training fit together, instead of treating everything as isolated techniques.

.

It’s based on the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. A grab, a punch, a stance, footwork – each is an individual element, but the real value comes from how they work together as a whole.

.

I believe it encourages students to understand rather than just repeat. Early training will always include repetition, but students should learn why and when a movement is applied, not just how to perform it. This moves them from being command-followers to people who can make intelligent choices in real time.

.

It isn’t the whole picture, of course. It just helps me teach people as people. Not everyone wants the same thing, so I don’t force them into one model. We find what works for them and move forward from there.

.

And that, to me, is part of good teaching. Not in copying the past without thinking, but in helping the person in front of you become better than they were yesterday.

.

At the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter what you call the theory. What matters is whether it actually helps the student understand and progress, and whether they know how to apply it when it matters most.

.

That’s our job, isn’t it? That’s the whole point.

.

.

Written by Adam Carter – Shuri Dojo

.

.

Photo credit: On the right, two of my students demonstrating an advanced interpretation of a basic ‘block’.